1982 marked a change in rallying for several reasons. One was the introduction of Group B, but another was that the battle between the Fiat 131 Abarth and the Ford Escort RS, which had raged for the previous four years, was finally over.

It had been a titanic struggle between two great teams. Fiat, a massive corporate organisation awash with sponsorship money, Ford, always appearing to be a day late and a dollar short. The Italian mechanics could sometimes seem anxious and disorganised, but were in fact thoroughly professional and willing to improvise. The British mechanics by contrast were usually dirty and dishevelled, but their machinery was always meticulously turned out.

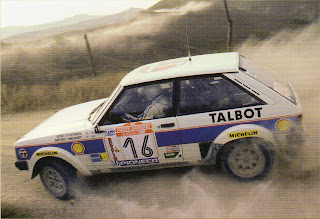

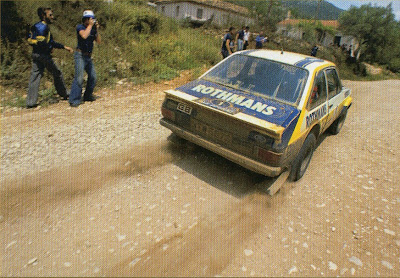

Their cars were superficially similar. Both were front engine, rear drive three box shapes loosely based on standard saloons. The Fiat was bigger, and with its squared off arches a bit weirder. The Escort had the more powerful engine, but also the simpler suspension. The Fiat therefore could boast better traction whilst the Escort was quicker to change direction. Both were tough, although the Fiat needed lots of extra reinforcement to survive rough rallies whilst the Escort turned out to have an Achilles heal in its head gasket.

Their cars were superficially similar. Both were front engine, rear drive three box shapes loosely based on standard saloons. The Fiat was bigger, and with its squared off arches a bit weirder. The Escort had the more powerful engine, but also the simpler suspension. The Fiat therefore could boast better traction whilst the Escort was quicker to change direction. Both were tough, although the Fiat needed lots of extra reinforcement to survive rough rallies whilst the Escort turned out to have an Achilles heal in its head gasket.Then there were the drivers. Fiat had the flamboyant Markku Alen - who in service areas would appear to be either about to have a nervous breakdown or kill someone - the amiable German Walter Rohrl and a whole galaxy of occasional drivers, hired and fired depending on the conditions.

Ford had a much smaller number of top drivers; the larger-than-like Bjorn Waldegard, the laid back Roger Clark, the earnest Ari Vatanen (they were space, grace and pace someone once quipped) and later the Finnish loose surface ace Hannu Mikkola.

The Escort had been homologated at the end of 1975 as the RS1800, replacing the RS1600 which used the Mark I Escort shell. It had show its pace immediately by winning the RAC rally. The Fiat was homologated at the start of 1976, replacing the 124 Abarth. The car did not have a promising start, only finishing one WRC event in the season, but that rally, the 1000 Lakes, it won outright.

In 1977, 78 and 79 both cars were entered by Works teams on World Rallies. At the end of 1979 Ford dropped out to build a new Escort, but they handed over all the Works bits, and the Works drivers, to David Sutton who continued to campaign them for the next two years.

With the arrival of the Lancia Rally in 1982 Turin finally pensioned off the 131 whilst David Sutton moved on to preparing Quattros. The battle was finally over.

The two cars first met on the 1976 Moroccan Rally. Alas it was an anti-climax. Both Ford's blew their engines whilst the Fiats had almost everything except the engine break. Two Fiats retired whilst Alen survived to finish twelfth. The 1000 Lakes two months later was rather more exciting. The spoils went to Alen in the Fiat. Vatanen stuffed his Works Escort into a tree, Makinen was off the pace in fourth, but clinging on behind Alen was Penti Airikkala in an Escort. A private Escort. Not for the last time a private Escort had beaten the works cars.

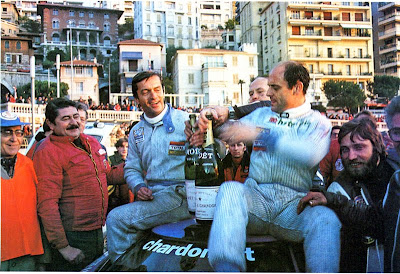

Ford again won the RAC that year, but 1976 was really just curtain raiser for the main event the next year. 1977 was to be the all out battle royal between the teams. Lancia won the Monte Carlo and Saab the Swedish, but after that no other team got a look in. Fiat eventually won the title on the Tour de Corse. They had outspent Ford by a considerable margin, but in the end it had gone down to the wire.

1978 looked like more of the same, but Ford quickly got cold feet an then lost most their program to industrial action.

In 1979 they came back booted and suited with a specialist tarmac Escort for the Monte. Engine and axle locations were moved to the extent that the car almost became mid-engined and the BDA was tuned to give more power than a Stratos. Victory was denied Ford by the ever friendly French spectators who placed rocks on the road, but it was a private Stratos that won, not a Fiat. Turin had lost on a rally they consider their own and Ford were on a roll. They lost the Swedish to a Saab, but that was enough for Fiat who threw in the towel and played truant for the rest of the season. Ford won the Makes championship and Bjorn Waldegard became the first ever Drivers champion.

In 1979 they came back booted and suited with a specialist tarmac Escort for the Monte. Engine and axle locations were moved to the extent that the car almost became mid-engined and the BDA was tuned to give more power than a Stratos. Victory was denied Ford by the ever friendly French spectators who placed rocks on the road, but it was a private Stratos that won, not a Fiat. Turin had lost on a rally they consider their own and Ford were on a roll. They lost the Swedish to a Saab, but that was enough for Fiat who threw in the towel and played truant for the rest of the season. Ford won the Makes championship and Bjorn Waldegard became the first ever Drivers champion.For 1980 David Sutton took over and whilst their was nothing wrong with his cars, the drivers didn't have a good year and Fiat took both titles. In 1981 though Ari Vatanen finally became the driver everyone had always hoped he would be and became Drivers champion. Fiat won their last World Rally in Portugal, whilst in Greece and Finland it was Vatanen and Ford first with Alen and Fiat second. Vatanen also won in Brazil, which only counted for the Driver's championship, and that was that. Battle over.

Between them these two cars pretty much dominated for half a decade, but before we tally up the final score, it's interesting to consider the rallies they didn't manage to win.

The Escort never won the Monte Carlo, but that wasn't for want of trying. In 1979 Ford got first Mikkola and then Waldegard into the lead, only to have them delayed by first French officials and then French spectators respectively.

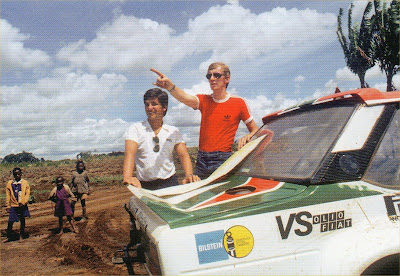

Fiat, unlike Ford, never managed to break the Saab stranglehold on the Swedish and they only made a single attempt on the Safari where, predictably, they suffered terrible disasters.

The Escorts failed to make a serious effort in Sanremo in '75 after the Dunlop tire lorry broke down on the way there, and Fiat defeated them on both Italian and Corsican tarmac in '77. They planned revenge the next year but the workers went on strike instead.

Alen meanwhile made competitive times in the 131 on 1976 RAC, but the big car was never suited to the British secret stages and by the end Alen was entering in a Stratos instead.

Alen meanwhile made competitive times in the 131 on 1976 RAC, but the big car was never suited to the British secret stages and by the end Alen was entering in a Stratos instead.Apart from that both cars more or less won everything worth winning.

The final scored was 18 WRC victories to Fiat and 17 to Ford, three Makes Championships to Fiat and one to Ford, one Drivers Championship to Fiat but two to Ford. Had the World Championship for Drivers started before 1979 each team would have racked up an extra title: Bjorn Waldegard for Ford in 1977 and Markku Alen for Fiat in 1978.

So Fiat would appear to have ended slightly ahead, but only slightly, and they did spend a lot more money on the project than Ford. However in one key respect Ford could claim the Escort was the winner. With the end of the factory team, the 131 Abarth pretty quickly disappeared. The specialist Abarth parts it needed were never made in large numbers and only the Works team and favoured privateers could get them.

So Fiat would appear to have ended slightly ahead, but only slightly, and they did spend a lot more money on the project than Ford. However in one key respect Ford could claim the Escort was the winner. With the end of the factory team, the 131 Abarth pretty quickly disappeared. The specialist Abarth parts it needed were never made in large numbers and only the Works team and favoured privateers could get them.Probably no more than 50 Abarth 131s ever entered rallies.

The Escort meanwhile has gone on to become the most ubiquitous rally car of all time. Ford had always been generous to private entrants, and even before the Works team was wound up RS parts were being officially and unofficially knocked out by a cottage industry of car tuners. Even now, 30 years since the car was officially retired, you can still build an authentic Escort RS yourself from any Mark Two shell. There's even a company that will build you a replica of the hottest Escort RS of all, the 1979 tarmac specials.