1982, and Audi look set to dominate the world of rallying. The team have learnt from the teething troubles of last year and with no other competitive four wheel drive cars on the horizon the predominantly loose surface WCR looks to be theirs. The Manufacturers crown is in the bag, the only question is who will lift the Drivers title. Will it be flying Finn Mikkola or will the macho world of rallying have to wake up to a lady champion in the shapely form of Michelle Mouton, last year's Sanremo winner.

The championship itself moved on in two ways. Firstly there were new rules: Group B had arrived. For the Monte Carlo these were just old Group 4 cars with new homologations, but exciting things were on the way. Also however, for the first time, a team actually entered every round of the championship. No single driver started every event - that was not humanly possible with the length of rallies in those days, but Opel were there at every round.

Opel's Ascona may have been an old fashioned two wheel drive model in its third season, but they now had Rothmans sponsorship and the former World Champion Walter Rohrl. Having been forced to take a sabbatical in 1981 due to an excess of honesty with Mercedes, he was now trying another German team.

The partnership immediately brought success. The previous year on the Monte Mikkola's Audi had been pulling away from the field at a minute a stage and they started as firm favourites to win this year. However they hadn't counted on Rohrl and his secret weapon - his handbrake. The Quattro's primitive four wheel drive system with it's locked central differential didn't allow handbrake turns. Added to the Quattro's hammer like weight distribution it meant the Audi was unable to change direction quickly if it hit a patch of ice. Rohrl beat Mikkola by a comfortable margin whilst Mouton lacking a working handbrake, and Rohrl's superhuman reflexes, hit a house.

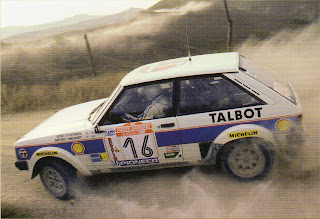

Sweden was Quattro country but it was local boy Stig Blomqvist who won, demonstrating how the skills he had learnt hustling bulky Saabs down the stages could be used to make the Quattro dance. Mouton won on the gravel of Portugal and again in the dust of the Acropolis. Mehta's Datsun (now called a Nissan) again won on the Safari whilst in New Zealand Toyota stopped being the bridesmaid and scored a one-two with the Celica after the Quattros failed.

Corsica meanwhile had proved the most technically interesting rally of the year with the appearance of not only Bernard Daniche in a 400 bhp plus BMW M1, but the new Group B Lancia 037 Rally. The rally itself turned into a thrilling dice between Ragnottis little Renault 5 Turbo, which liked the tighter stages, and Andruet's big Ferrari 308GTB, which preferred the faster ones, with victory eventually going to the more nimble Renault. The Lancias had handled diabolically and Attilio Bettega was hospitalised after a serious accident. Group B had arrived and had shown how exciting, and dangerous, it was going to be.

Rohrl meanwhile had had a steady season after the Monte finishing best non-Scandinavian in Sweden, best non-Nissan on the Safari, best conventional car in Corsica, best non-Audi in Greece and best non-Toyata in New Zealand. He'd suffered high speed steering failure in Portugal and missed Finland. The result was Opel led Audi 88 points to 58 in the Manufacturers series whilst Rohrl led Mouton 84 points to 52 in the Drivers.

The round in Argentina was cancelled due to some unpleasantness on the Falkland Islands so there were five rallies left in the Drivers championship and four in the Makes. Superficially things looked good for the Rothmans team, but there were problems. Firstly all the remaining rounds were wholly or predominantly on gravel. Secondly the series had a 'best seven' rule which meant only the top seven results counted towards the final tally so steady performances weren't going to be enough, Opel had to win something.

The next round was Brazil and things started to look ominous for Rothmans. Rohrl said he's never driven harder on a gravel rally. Certainly he'd never driven harder and lost and it was victory for Mouton and Audi. Rohrl skipped the 1000 Lakes to practice for Italy. Victory went to Mikkola's Quattro but crucially Mouton ended up on her roof and so she didn't score either.

Sanremo was next, a mixed tarmac and gravel event. The first days stages were on tarmac and the Audis found themselves behind a Ferrari and Alen who was flying in an Evolution 037. Once on the gravel though the Audi hordes, which includes Blomqvist in his Swedish Quattro, Harold Demuth in his German one and local boy Michele Cinotto in another, started to blitz the opposition. The rally returned to tarmac but still as we went into the last night, Audis held the top four positions with Rohrl down in seventh. That last night was to be one to remember. Rohrl overhauled first Demuth, then Cinotto and then crucially Mouton. Team mate Toivonen had a puncture and so Rohrl passed him too to finish third. Blomqvist, who was rapidly proving to be the fastest Quattro driver of all, won, but Opel had done enough to keep both championships alive.

The series then moved to the forests of West Africa, where the Ivory Coast rally looked like being interesting for the first time in its short and troubled history. Audi had never been to Africa, but they learnt fast and soon Mouton was leading with Mikkola, who had team engineer Roland Gumbert to act as 'flying mechanic', second. But Mikkola hit trouble and soon Rohrl was snapping at Mouton's heals. Victory would have left Mouton two points behind Rohrl with only the RAC to go.

At 4AM on Monday 1 November the rally restarted for a final seven hour blast to the finish. Mouton was 18 minutes ahead, but that lead was immediately wiped out when the Quattro wouldn't start. The French lady eventually got going but fog had descended and she left the road. She got going again but her co-driver had lost the pace notes and she had to drive blind - not easy in fog, especially as African roads then weren't actually closed and you could (and did) meet traffic coming the other way. It was a brave drive, but too much for her. A confusingly marked crossroads did for her and the car was too badly damaged to continue. Rohrl won and collected the Drivers Championship. Next year he had signed for Lancia so on the eve of the RAC Opel rewarded him for his efforts by giving him the sack.

The RAC went to Mikkola's Quattro. Toivonen tried hard for Opel but could only manage third, giving Audi the Manufacturers crown. For a while though the Audis were headed by Alen in his little Lancia. The Italians were clearly planning to take the battle to the Germans for 1983.